NOTE: this is another in a series of chapter drafts to be included in the book ALTERNATIVE APPROACHES TO WRITING: A MIXED-RACE WRITER’S JOURNEY (tentative title). This particular chapter took me in a direction I wasn’t planning on traveling, thus the road is windy and full of rocks-the key word as always, draft (and why when I cut and paste does the formatting change?).

RESPONSIBILITY

In the beginning of any particular semester, I might ask my students what is the responsibility of a writer?—not if a writer has responsibility. I might ask them to read “The Creative Process” by James Baldwin (Creative America, 1962), the poem “Responsibility” (New and Collected Poems) Grace Paley, and/or “Meatloaf: A View of Poetry” by Nikki Giovanni (Racism 101, William Morrow and Company, Inc.). Discussions are generally mild, and don’t go beyond two pat answers: to entertain and to tell the truth.

I’m not interested in writing to entertain, perhaps because my sense of humor is limited, my ability to write humorously is deficient (though I’ve been told my writing is often sassy or witty)—and what I write about, my life, is too serious to joke around with (granted some comedians can put a comedic twist on anything with grace, others not so much).

However, as Joy Harjo states in The Woman Who Fell from the Sky (First published as a Norton paperback, 1996):

If I am a poet who is charged with speaking the truth (and I believe the word poet is synonymous with truth-teller), what do I have to say about all of this?

I believe truth can be expressed in several ways: metaphor, exaggeration, and plain and simple in-your-face clarity. Each or all of these forms can be used no matter what genre we are writing in. Because I began my writer’s journey as a poet, I learned the craft of figurative language and eventually became aware of how I can/how I do use it in my writing.

A poetry teacher frequently told me my poems are filled with imagery; I had no idea what he was talking about. Now I realize metaphors and similes create pictures that are understood by way of comparison. And the magic is that a reader can, and most likely will, transcribe the picture with the help of his/her own experience, so the writer has made a connection beyond his/her reality.

The more I write, the more I notice I exaggerate the truth. I am not lying. It’s like hyperbole. I am extending concrete fact into superfluous images. Exaggeration may be expressed as metaphor; for example I’m not like all the Scandinavian friends I grew up with:

Here I am a Minnesota mutant.

Snowflake.

Or, as a statement I know isn’t true to fact, but true to the point I want to get across:

Mother cooked a white rabbit

in a black pot.

Mother never cooked rabbit, but mother who is black, chose to pass as white. I don’t consider the exaggerated image a lie.

Or, I use words that play with imagery that exaggerate the meaning:

My sisters and I rip out the tight stitches, laugh about the alcohol, the men.

Instead of saying my sisters and I gave up our mother’s control , I use the more visual aspect of stitches which refer back to earlier in the poem that tells the reader my mother sewed identical clothes for her four daughters.

Although imagery enlivens a story or poem, I believe if a writer doesn’t want a reader to misinterpret what they’ve written as truth, the writer should be explicit in the language they use. This type of honesty is so blatant those that can relate will appreciate or be awed by your downright honesty; those that can’t relate will be offended or defensive or apologetic—but, you’re not writing for them, or are you (that’s another discussion)?

Husbands were always white, always financially able—always available. They liked me sexy. They liked me smart. They liked me domestic. They liked me drunk. They were always gratuitous. I ate meat and potatoes. I lived in brick houses. I owned stuff

…Husband after hedonistic white husband enjoyed associating with me, the marginalized. Because, of course I was trendy. Yet each hunkered down, holding their top dog position.

But, what is it we, as writers, are supposed to tell the truth about? As a writer trying to discover and make sense of who I am, I had no time for nature poems. Aren’t there more important stories that need to be told? Don’t we as writers have the responsibility to tell them?

The artist cannot and must not take anything for granted, but must drive to the heart of every answer and expose the question the answer hides.—James Baldwin

It is the responsibility of the poet to say many times: there is no

freedom without justice and this means economic

justice and love justice –Grace Paley

Nikki Giovanni wrote:

I have seldom read an interesting poem about the discovery of raindrops, or clouds floating by, or sunsets either…

I hope, … that I am showing my students they must contemplate the world in which they live. I believe their responsibility as writers is to have as much sympathy for the rich as for the poor; as much pity for the beautiful as for the ugly; as much interest in the mundane as the exotic….Look; allow yourself to look beyond what is, into what can be, and more, into what should be.

Never say never, my sister always tells me. When I discovered Mary Oliver’s poems, Linda Hasselstrom’s essays, and Scott Russell Sanders essays, and other writings which do contemplate the world, I knew the responsibility of the writer is also to read and not let our preconceived notions keep us from imagining and knowing a world larger than our own. However, as I wrote this paragraph I realized I only mentioned white writers who write about nature. Why haven’t I read nature writing by writers of color? Subconsciously I probably thought we have more important things to write about—but I immediately Googled what writers of color write about nature? And despite my bad grammar, here’s the first two entries I found:

- Colors of Nature Culture, Identity and the Natural World, edited by Lauret E. Savoy, Alison H. Deming (Milkweed Editions; Second Edition edition (February 1, 2011); and,

- “Toward a Wider View of ‘Nature Writing’” by Catherine Buni, The Los Angeles Review of Books, January 10, 2016.

Buni writes:

In 2009, [Camille T.] Dungy published Black Nature, a beautiful, widely influential, and redefining anthology of African-American nature poetry. Spanning over 400 years, 180 poems by 93 poets…

But Dungy continues:

The most vulnerable are the least powerful, so they get the least coverage, and certainly the least precedent-changing publication.

Thus, We have been contemplating nature and writing about it (or oral story-telling), but access has been limited.

Now, thanks to my curiosity and Catherine Buni’s in depth essay, I have a few more books to add to my Want to [need to] Read list on Goodreads (https://www.goodreads.com/) —including Black Faces, White Spaces: Reimagining the Relationship of African Americans to the Great Outdoors, by Carolyn Finney (The University of North Carolina Press, June 2014).

To Lori, a former student, I apologize. I will not discourage another student from writing nature poems. Actually, I have written a couple of them myself.

Writing Exercise:

- What do you believe is your responsibility as a writer?

- Search through some of your stories and poems to discover how you have crafted truth. Do you use metaphor, exaggeration, or hard honest fact?

- Read: read something outside of your interest and, perhaps, comfort zone.

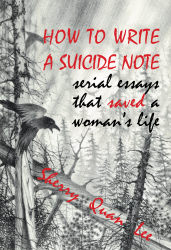

©Sherry Quan Lee, March 20, 2016